A.I. and You

I subscribed to Spotify a few months ago and I am enjoying it. I bought a good digital/analogue conversion box last January and I have a good quality USB connection with my laptop. The quality of the sound is quite listenable. And I like that I can find almost any artist. What I find humorous though are the suggested playlists the algorithms produce. Spotify does not really know me very well . . . at least . . . yet.

That's fact #1 for this article.

My dad was an unusual character in many ways, but one of them was that he was truly a math guy. When I was growing up he worked as the head of the "actuarial" department of a medium-sized general insurance company. We've heard the word "accountant" often, but many of us have probably never encountered the word "actuary". If accountants look at the present and the past, actuaries look at the future by analyzing the past with carefully constructed stats.

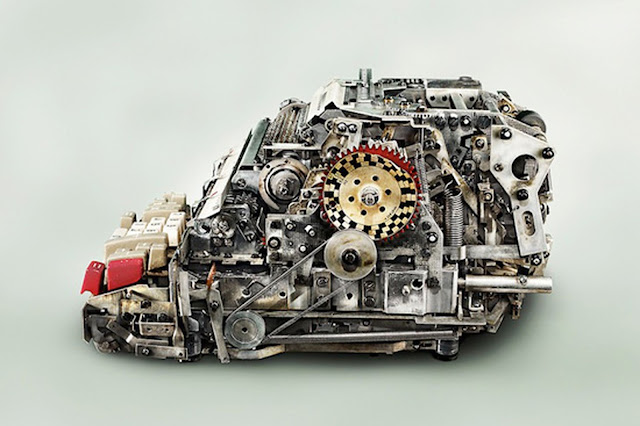

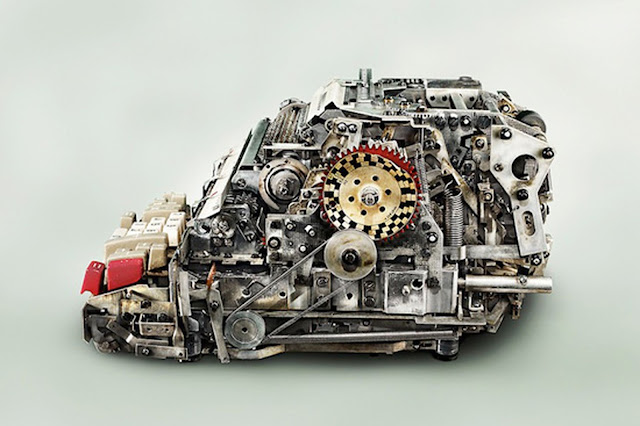

When he was starting in this business, he literally was using a slide rule. You might have to look that up on Wikipedia. Main frame computers were coming into use as my age was approaching double digits. After the Santa Claus parade we always stopped at dad's office. For me, it was to see the equipment; for my parents it was so that the kids could go to the bathroom. I remember using a mechanical calculator that looked similar to an old cash register. It had a bewildering set of related gears -- and I mean probably a couple of hundred. Long division was very exciting for a mechanically-minded kid. As it made the calculation there were clunks and thunks at varied rates and intensity, and after about 4 seconds it stopped. The result was visible on the wheels displaying the numbers. In his last decade of work, dad learned six programming languages. Looking back, that's the more awesome bit.

That's fact #2. Now a little background and some application.

That's fact #2. Now a little background and some application.

Actuarial science has been used by the insurance industry as the principal way that insurance premiums, re-insurance strategies, and cash reserves required by government regulation, have been calculated. As computerization has broadened in use and become more powerful, the application of the actuary's skills of statistical analysis and design have come to be applied in an increasing number of areas. They are used extensively now by mutual funds, for example. And, I suspect they are an integral part of AI design.

It is interesting that we are adopting the use of the term "artificial intelligence". It is an application of intelligence in a way that is artificed. That's true . . .

When I was asking my dad about his use of computers he tended to use a very simple and direct language: "Garbage in, garbage out." A program is only as good as its programmer. Now that we all use extremely elaborately coded programs which operate on extremely elaborate operating system which require the contributions of armies of programmers, we take what the computer can do for granted.

It has been quite shocking to fact-oriented me that the rise of social media seems to have magnified human gullibility so that we flap our wings about all sorts of things that either may not be true or which are being misused or cast in a very restricted light.

So we should have some pause about A.I. Sophisticated programmers can certainly have their way with us. Unlike the mechanical calculator, the workings of which I could actually see and take apart if I wanted, the workings of the apps we use and the arrival of the internet of things are not visible to us. Perhaps we are seeing an instinctive reaction of disbelief that is vibrating these days in public life.

Those who take a full-time interest in these things and who haven't been romanced by them, are asking questions. How do we evaluate "bias" within the algorithms? Theoretically there will always be bias until we have a computer that is like the "Borg" from Star Trek or more powerful than "Hal" from 2001 A Space Odyssey. The idea of even speaking about ethics in these matters seems to be lagging far behind. Are we not more important than the machines we use. It certainly is unjust if it is machine that is using us.

How AI is shaped and used can and should still be a subject that looks to the service of humanity rather than the inevitability of progress for its direction. In a world where we have become specialized and occupy differing "universes" and world views there is real food for human conflict if we are not careful.

For a short time, the term "fuzzy logic" was applied to this area of computer development. I kind of like it better, because it says more clearly what is going on. Strict "B" follows "A" is not being applied and an alternative output is being selected based upon a mathematical probability designed by a person (or persons together). It is a probability game and it is precisely because computers can crunch through numbers and calculations at very high speeds that this is possible. And it is very helpful in many ways. But we shouldn't leap to the conclusion that we are no longer needed and life would be exceptionally dull if we were not. And if we are being used more than directing the use of this information in some way we have become a sideline. It is ironic that "privacy policies" are the umbrella under which the use of this information is being disclosed. Surely, it is the reverse. What loss of privacy are we willing to surrender for what benefit? With the size of the companies involved, we, at least as individuals, are at a decided disadvantage.

My music collection teaches me that. I find Spotify lacks some albums of artists I know and like, and believe it or not, there are CD's out there and LP's too that have small audiences that may never see Spotify. Like tasting a good wine from a small winery, what a shame if you deny yourself the opportunity. When I go to my old CD shop, I talk to the owner and graze through discs without the eye fatigue of a screen and far more able to evaluate what I would like to look at without Spotify or Apple putting what it thinks I would like to see in front of me. In fact, it may come as a surprise, but I suspect that Spotify and Apple put in front of me what they would like me to buy. With their statistical analysis they are quite possibly calculating their chances are pretty good. But what if I mature today or encounter a real person whose musical love or insight nudges me to something that will make me more whole rather simply following what is expected by those marketing to me?

As much as TV "sucked us in" in the '60's and '70's, the interactive quality of the internet and the short-range focus required to look at our "smart" phones seems to me to be much more powerful. Nothing short of our souls are at stake. What is the good that God (and not some algorithm) desires of me today?

That's fact #1 for this article.

My dad was an unusual character in many ways, but one of them was that he was truly a math guy. When I was growing up he worked as the head of the "actuarial" department of a medium-sized general insurance company. We've heard the word "accountant" often, but many of us have probably never encountered the word "actuary". If accountants look at the present and the past, actuaries look at the future by analyzing the past with carefully constructed stats.

When he was starting in this business, he literally was using a slide rule. You might have to look that up on Wikipedia. Main frame computers were coming into use as my age was approaching double digits. After the Santa Claus parade we always stopped at dad's office. For me, it was to see the equipment; for my parents it was so that the kids could go to the bathroom. I remember using a mechanical calculator that looked similar to an old cash register. It had a bewildering set of related gears -- and I mean probably a couple of hundred. Long division was very exciting for a mechanically-minded kid. As it made the calculation there were clunks and thunks at varied rates and intensity, and after about 4 seconds it stopped. The result was visible on the wheels displaying the numbers. In his last decade of work, dad learned six programming languages. Looking back, that's the more awesome bit.

That's fact #2. Now a little background and some application.

That's fact #2. Now a little background and some application. Actuarial science has been used by the insurance industry as the principal way that insurance premiums, re-insurance strategies, and cash reserves required by government regulation, have been calculated. As computerization has broadened in use and become more powerful, the application of the actuary's skills of statistical analysis and design have come to be applied in an increasing number of areas. They are used extensively now by mutual funds, for example. And, I suspect they are an integral part of AI design.

It is interesting that we are adopting the use of the term "artificial intelligence". It is an application of intelligence in a way that is artificed. That's true . . .

When I was asking my dad about his use of computers he tended to use a very simple and direct language: "Garbage in, garbage out." A program is only as good as its programmer. Now that we all use extremely elaborately coded programs which operate on extremely elaborate operating system which require the contributions of armies of programmers, we take what the computer can do for granted.

It has been quite shocking to fact-oriented me that the rise of social media seems to have magnified human gullibility so that we flap our wings about all sorts of things that either may not be true or which are being misused or cast in a very restricted light.

So we should have some pause about A.I. Sophisticated programmers can certainly have their way with us. Unlike the mechanical calculator, the workings of which I could actually see and take apart if I wanted, the workings of the apps we use and the arrival of the internet of things are not visible to us. Perhaps we are seeing an instinctive reaction of disbelief that is vibrating these days in public life.

Those who take a full-time interest in these things and who haven't been romanced by them, are asking questions. How do we evaluate "bias" within the algorithms? Theoretically there will always be bias until we have a computer that is like the "Borg" from Star Trek or more powerful than "Hal" from 2001 A Space Odyssey. The idea of even speaking about ethics in these matters seems to be lagging far behind. Are we not more important than the machines we use. It certainly is unjust if it is machine that is using us.

How AI is shaped and used can and should still be a subject that looks to the service of humanity rather than the inevitability of progress for its direction. In a world where we have become specialized and occupy differing "universes" and world views there is real food for human conflict if we are not careful.

For a short time, the term "fuzzy logic" was applied to this area of computer development. I kind of like it better, because it says more clearly what is going on. Strict "B" follows "A" is not being applied and an alternative output is being selected based upon a mathematical probability designed by a person (or persons together). It is a probability game and it is precisely because computers can crunch through numbers and calculations at very high speeds that this is possible. And it is very helpful in many ways. But we shouldn't leap to the conclusion that we are no longer needed and life would be exceptionally dull if we were not. And if we are being used more than directing the use of this information in some way we have become a sideline. It is ironic that "privacy policies" are the umbrella under which the use of this information is being disclosed. Surely, it is the reverse. What loss of privacy are we willing to surrender for what benefit? With the size of the companies involved, we, at least as individuals, are at a decided disadvantage.

My music collection teaches me that. I find Spotify lacks some albums of artists I know and like, and believe it or not, there are CD's out there and LP's too that have small audiences that may never see Spotify. Like tasting a good wine from a small winery, what a shame if you deny yourself the opportunity. When I go to my old CD shop, I talk to the owner and graze through discs without the eye fatigue of a screen and far more able to evaluate what I would like to look at without Spotify or Apple putting what it thinks I would like to see in front of me. In fact, it may come as a surprise, but I suspect that Spotify and Apple put in front of me what they would like me to buy. With their statistical analysis they are quite possibly calculating their chances are pretty good. But what if I mature today or encounter a real person whose musical love or insight nudges me to something that will make me more whole rather simply following what is expected by those marketing to me?

As much as TV "sucked us in" in the '60's and '70's, the interactive quality of the internet and the short-range focus required to look at our "smart" phones seems to me to be much more powerful. Nothing short of our souls are at stake. What is the good that God (and not some algorithm) desires of me today?